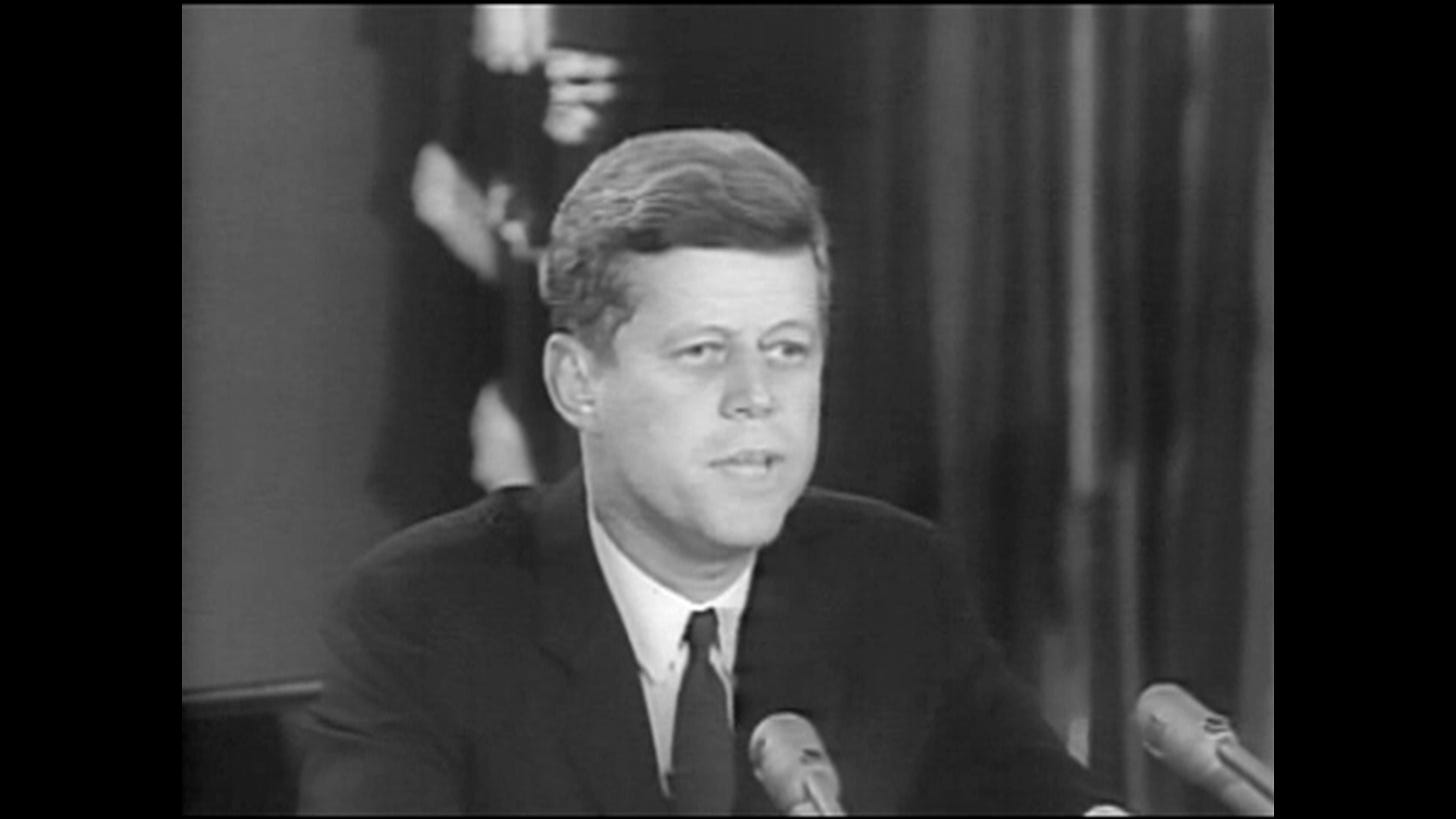

61 Years Ago Today: JFK Prepares Cuban Crisis Speech--And Discovers Loose Control of Our Own Nukes

One of our generals could have launched missiles on his own...

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books and now writer/director of award-winning films. He was the longtime executive editor of the legendary Crawdaddy. His newsletters (see also this one on music and politics) remain free when you subscribe. His film “Atomic Cover-up” became free via Kanopy this month and the current “Memorial Day Massacre: Workers Die, Film Buried" remains free on the PBS site. Both have companion books.

Continuing a series begun earlier this week, as we look back 61 years this week to the gravest nuclear crisis of our era, involving JFK, Castro, and Soviet missiles in Cuba. The below is an excerpt from my 2016 bestseller, The Tunnels: Escapes Under the Berlin Wall, which among other things revealed the Kennedy White House trying to kill, that same autumn, one of the most important TV specials ever, from NBC, documenting a perilous underground passage to freedom.

Note: As I have long said, U.S. nuclear "first-use" or “first-strike” policy remains in effect today, as dangers in the Middle East proliferate this month….

Also: A name change for this newsletter since it seems to be outlasting and maybe outgrowing the fervor around the “Oppenheimer” movie. So, instead of “Oppenheimer, from Hiroshima to Hollywood” it is now “Oppenheimer and the Legacy of his Bomb.”

President Kennedy was getting ready to deliver a nationwide television address. In the latest draft, crafted mainly by Ted Sorensen, he referred to Berlin only briefly, but with emphasis: “Any hostile move [by the Soviets] anywhere in the world against the safety and freedom of peoples to whom we are committed—including in particular the brave people of West Berlin—will be met by whatever action is needed.”

In discussions and debates with top aides and military advisers over the past two days, President Kennedy had stuck to his decision to issue an ultimatum to the Soviets to remove all its missiles immediately, along with the blockade of Cuba, before taking military action. But he would wisely refer to the blockade as a “quarantine,” to distinguish it from the only blockade most Americans were familiar with—Berlin, 1948, by the Soviets—while communicating that only offensive weapons, not fuel, food or medicine, would be halted. Forty U.S. ships were already in position to enforce it. In any case, if the Soviets challenged the blockade or flatly ruled out removing the missiles, U.S. air strikes would be swift and strong.

A few days had now passed since the Washington Post learned about the discovery of nuclear missiles in Cuba, but the President had asked editors to hold off on revealing this until his televised speech, and the Post complied. Other media fanned the fears provoked by rumors. Lester Bernstein’s family in New York, knowing that he was still in Berlin—sure to be one of the world’s most endangered cities in coming days—grew particularly worried. And they didn’t know that the Berlin Mission chief and at least one other official there had already evacuated their wives and children to America.

As the afternoon wore on, U.N. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson cabled Dean Rusk: “I believe decisions must be made before this evening about how we will react if the USSR in the next few days seeks to interfere with our access to Berlin. Decisions need to be made both with respect to our physical reaction in the area and what to do in the UN.”

Kennedy was also concerned about the chain of command if the U.S. was tempted to respond to a Soviet attack by firing nuclear missiles. He assumed that our missiles closest to Russia, in Turkey and Italy, could only be fired after a specific order from him. This turned out to be untrue. The local U.S. commanders had been given that power under standing orders. Not only that, when JFK told one of the Joint Chiefs in a meeting that afternoon that he didn’t want any missiles fired without his express approval, the general seemed to balk. A few minutes later, when the President brought this up with Paul Nitze, an assistant Secretary of Defense, he again met resistance.

Over the course of the day it became clear that Kennedy and other top officials were not completely up to speed concerning our nuclear forces and their possible use. Dean Rusk, for example, asked Nitze, “The ones in Turkey are not operational, are they?”

“Yes, they are,” Nitze said.

“Oh, they are,” Rusk said, dryly.

“Fifteen of them are on alert right now,” Roswell Gilpatric added.

Seconds later, Nitze pointed out that NATO policy called for the automatic launch of such missiles in the event of a Soviet strike, “according to its EDF.”

“What’s EDF?” President Kennedy inquired

“The European Defense Plan,” Nitze responded, “which is nuclear war.”

Kennedy coolly replied that this might be fine if it came to a wide-scale Soviet attack, but not a “spot” one. He insisted again: Tell the commanders that I am in charge. This time Nitze said he’d do it.

In a meeting to inform congressional leadership about his coming speech, JFK heard Sen. Richard Russell, the top Democrat on the Hill, argue for a U.S. strike on Cuba, asserting that we had to “take this gamble” even if it risked nuclear war. The leading Democratic senator on foreign policy, J. William Fulbright, slammed the blockade and called for “an invasion and an all-out one.”

At 7 p.m., the President went on the air with his historic “quarantine” speech, as written. And then he, and the world, waited.

Complete speech:

I remember my family making plans to use my grandparents' basement as a not very good fallout shelter. We were terrified!