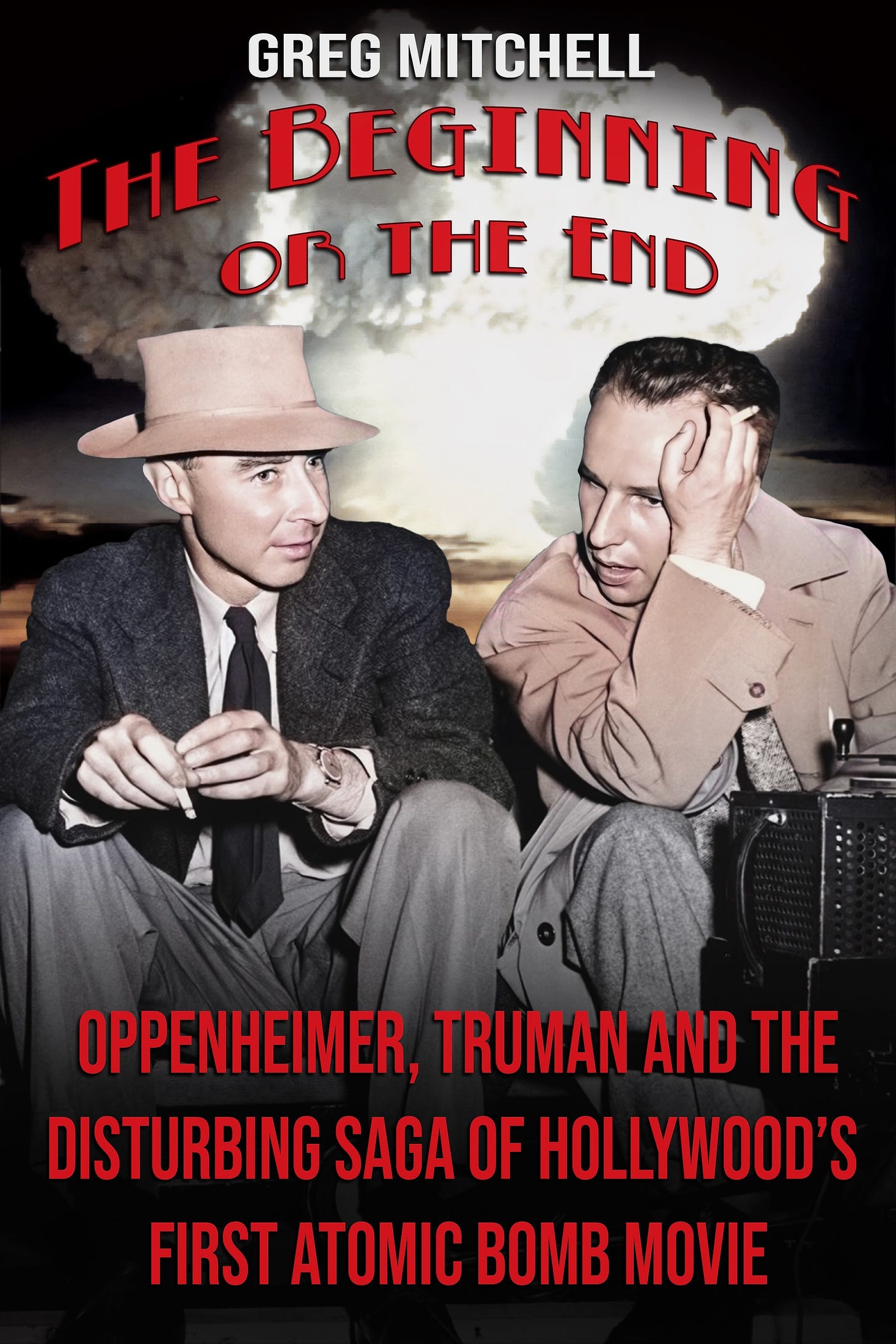

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including “Hiroshima in America,” “Atomic Cover-up,” and the recent award-winning “The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood—and America—Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.” He has directed three documentary films since 2021 for PBS (and “Atomic Cover-up” coming this fall). He has written widely about the atomic bombings for over forty years. You can subscribe to this newsletter for free.

Seventy-seven years ago this week, an article by novelist and war reporter John Hersey (photo above), titled simply "Hiroshima," occupied the entire feature section of the August 31, 1946, issue of The New Yorker.

Soon it would be hailed by many as one of the most important magazine stories of the century. Its impact, arriving at a time when few Americans had been exposed to the extent of the atomic bomb's horrific and lingering effects on Japanese civilians, was immediate and profound. (I wrote about it twice here last week.) Copies sold out within hours (Albert Einstein himself ordered a thousand); it was read in its entirely over nationwide radio.

For officials and military leaders who took part in the decision to deploy the new weapon over the center of two cities, killing over 200,000 (the vast majority of them civilians), however, the Hersey piece posed a threat to the narrative they had promoted on why this use was necessary. But what did the man with ultimate responsibility for that, President Harry S. Truman, think about the article?

The White House was already pressuring MGM to make sure that its forthcoming movie drama, The Beginning or the End (explored in my book) painted the president and his decision in a positive light. Those close to Truman, however, had largely remained silent about the Hersey article. They didn't want to stir controversy and draw even more attention to it.

Then, on October 7, 1946, Leonard Lyons reported in his widely syndicated daily gossip column:

A White House visitor asked President Truman: "Did you read the Hiroshima piece?" He said: "What was that?" and the visitor told him: "The John Hersey piece in The New Yorker." Mr. Truman replied: "I never read The New Yorker. Just makes me mad."

Bemused, or maybe a little perturbed, famed New Yorker editor Harold Ross two days later sent Truman press secretary Charles Ross (no relation) at the White House three copies of the issue which contained the Hersey opus, along with a clip of the Lyons item. The editor explained simply that he felt the article was "one that should be read by all the influential people in the world that can be got to read it." Would the press secretary read it himself and perhaps recommend it to the President? "I wouldn't have paid any attention to this," editor Ross explained, "but I was told by a Washington newspaperman today that he is certain President Truman had not [even] heard of it."

That would indeed make the president one of the relatively few in high government or intellectual circles who had not. Harold Ross added: "I think he ought to know about it."

Charles Ross replied quickly, claiming that he had read the article when it first came out and found it "magnificent." Ross, before becoming Truman's press secretary--he attended high school in Missouri with the president's wife, Bess--had a strong journalistic background. He had won a Pulitzer Prize for his reporting on Depression-era economic issues in 1932 for the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and then became editorial page editor of the paper.

Now he told the New Yorker editor he could not say whether or not Truman had read the piece but, in any event, he doubted that his boss ever said what Lyons had him saying. And surely if he did mutter that the magazine "just makes me mad" he had to be referring to another publication! Now, in any case, he would make sure Truman received a copy of that issue. He asked Harold Ross to keep all this hush-hush.

The magazine editor replied immediately, revealing that a staffer had written a small piece on the Lyons report but now he might decide not to publish it because it might not be "fair" to the president. But he still hoped Truman would read the article. "There is, of course, a feeling of holy zeal about the Hiroshima piece in this office," he explained, "and a hope that the leaders of all countries will read it. This feeling extends considerably beyond the office, as a matter of fact."

On October 22, 1946, Charles Ross informed Harold Ross that he had asked Truman point blank if he had ever said The New Yorker "just makes me mad" and he denied it. Truman added that he was happy to now have the Hersey piece (confirming that, indeed, he had not yet read it in the seven weeks since its heralded publication). "I may be able to make a New Yorker fan out him yet," the president's secretary declared.

There is no record in Truman's papers or elsewhere if Truman did read that issue or what he thought about it. What we do know is that Truman and aides ordered revisions and a costly full re-take in that MGM movie to bolster his case for using the bomb. In any event, he would argue (see my piece) that he "never lost any sleep" over his decision to drop the bomb.

Just published: an expanded edition of my book Atomic Cover-up, now with several thousand words of mine re: the movie and the man Oppenheimer. And it’s on sale this week as an ebook for just $3.99 ($12.95 for the paperback).

Even if Truman did read the Hersey piece, it would be difficult for him to say so publicly and then not follow-up with what he thought of the article.