Last night, returning from Manhattan after the Oppenheimer screening, I posted atop Saturday’s already-mailed newsletter a few general thoughts on the movie and a couple of highlights from the panel, with remarks by director Christopher Nolan.

An “embargo” on full reviews by actual film critics enacted by Universal remains in effect but I trust brief commentary and historical reflections/corrections such as the following are fine.

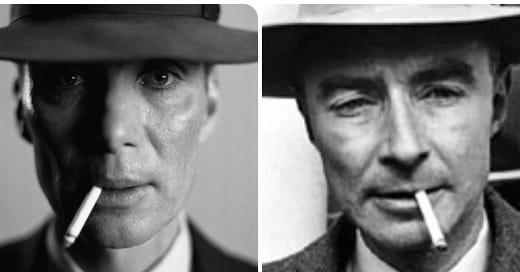

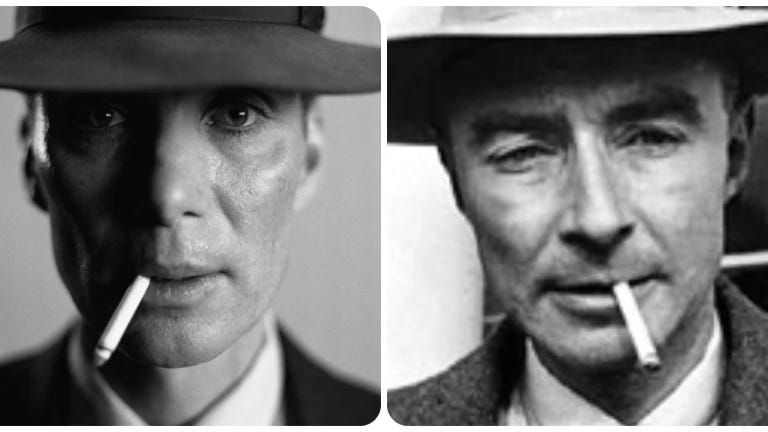

As I wrote last night, the movie is brilliantly directed and acted and is a technical wonder (as you may have heard). As my family will tell you, I hate ultra-long movies, but found no problem in this case, and the first two hours or so really fly by. Terrific script and sound design. The seemingly forced appearances of Einstein really pay off in the end. Nolan should be roundly thanked for tackling this difficult, sensitive, important, subject. And if I was an entertainment writer, I might say, “Cillian Murphy, meet Mr. Oscar!” But what about the content and emphasis?

As a kind of caveat for all that follows today and tomorrow: I’m not a typical viewer. I’ve written about Oppenheimer for decades (three books, hundreds of articles, etc.) but my focus has always been on the use of the bomb and its aftermath, not its invention at Los Alamos--nor the Trinity test, the fight over the H-bomb and his infamous security clearance hearing. As it happens, the atomic bombings, and what happened in the two Japanese cities, occupy very little overt time in the movie, especially compared to those other subjects (and even Oppie’s extra-marital affairs).

The other major character, former Atomic Energy Commission chief Lewis Strauss, says near the end that Oppie should thank him for helping to guarantee that people associate him more with the Trinity test (where no one died) than with Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But like other movies on Oppenheimer or the bomb’s creation, the Nolan film with its lengthy Trinity section also tilts in that direction, in minutes if not in its ultimately profound message.

Still, there are so many great moments, and as Nolan said at the post-screening panel, it does leave you with much to ponder in the hours and days that follow, and how many movies today inspire that? Nolan may go over the top in spots but also handles many key moments with subtlety. A very minor one that I loved: After taking over at Los Alamos we witness Oppie, rather absurdly, in an Army uniform—this did happen, under orders from General Groves, as he explains. A friend tells him it doesn’t suit him (so to speak) and he should just be himself. In the space of about 30 seconds we see Oppie basically create his iconic image: straightening a grey suit and tie, and donning what would become his trademark, a slightly Western felt hat and adjusting its broad brim, just so. Fade.

But how does the movie tackle some of the issues surrounding the decision to drop the bomb? The major failing is in not challenging the entrenched “Hiroshima narrative” that holds that the use of the bombs, and only the use of the bombs, ended the war. Now, this may not have been a priority for Nolan, who also wrote the fine script. What he no doubt set out to accomplish--and mainly he succeeded--was in picturing the development of Edward Teller’s “Super” (or H-bomb), which Oppie mainly opposed, as the true nuclear turning point, and how this haunts us today.

Nolan’s mind is more on 2023, not 1945. That’s fine in most ways, but I would argue, as I have for almost forty years now, that you can’t lower the chances of a nuclear attack in the future without truly coming to terms with the two times we have already used the bomb. As long as we endorse these exceptions—it’s easier for more to be made.

This is such an important issue, for the movie and for humankind, that I’ll save it for a major appraisal tomorrow or the next day.

Just two more notes for today.

>>Since today is the Day of Trinity: As I feared (see yesterday’s post), the movie, despite dwelling on the first test, does not depict or even refer to what happened after that blast—a radioactive cloud drifting over nearby settlements. Oppenheimer had worried about this but did nothing to stop it and agreed to keep records secret afterward. True, Nolan had to leave a lot out of his story, but in general the radiation, secrecy and cover-up components in the tragedy surrounding what happened in 1945, and in the nuclear era that followed, is unfortunately underplayed in the movie. Given how many “downwinders,” soldiers, workers, and millions of average American citizens would suffer for decades.

>>The script seems remarkably accurate in its details, although there are a number of things I need to check out. One scene I watched with particular interest was the infamous portrayal of Oppie’s visit with Truman about two months after Hiroshima. It’s far from a major flaw, but I mention it because it is a key moment in the movie, as Nolan wants to emphasize Oppenheimer’s growing regrets about the death toll in Japan (in real life the physicist’s record on this was decidedly mixed). This scene, like nearly all of Nolan’s, may work well with audiences, but it felt slightly off to me.

For one thing, an unrecognizable Gary Oldman chews the scenery and makes Truman a little too buffoonish—and I am no fan of Harry S. Secretary of State (and hardest of hardliners on dropping the bomb) Jimmy Byrnes, is there, and he was not. Oppenheimer makes an odd remark about turning the Los Alamos area back to the Native Americans, while riles Truman. It’s a great line, but invented, I believe. (If I am wrong about any of this, please tell me.)

Then the moment comes when Oppenheimer tells Truman that he fears he has “blood on my hands.” There are multiple versions, by historians and biographers, concerning this. In the simplest, Truman simply replies that if anyone does, it is him, and the discussion moves on. The more dramatic accountings have him taking out a handkerchief and wiping his hands, or giving it to Oppenheimer to clean his. Here Nolan chose a sensible middle ground, with Truman taking out the handkerchief, then just holding it.

The scene ends with Oppie leaving the office as Truman’s mutters this aside to Byrnes, “Don’t let that crybaby come here ever again.” Truman did express this order, but to another man, and the “crybaby” appeared in one of his letters and was actually “crybaby scientist.” Taking liberties with all this, and with the usual compression, works in the script, however, and I’ll leave it at that.

Much more tomorrow!

Excellent as usual. You have convinced me to see the movie when it reaches my local theater.

On what evidence do you base this statement?--> “Given how many “downwinders,” soldiers, workers, and millions of average American citizens would suffer for decades.” I know of none.