It’s in vain to recall the past, unless it works some influence upon the present.— Charles Dickens

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including “Hiroshima in America,” “Atomic Cover-up,” and the recent award-winning “The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood—and America—Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.” He has directed three documentary films since 2021, which have all aired over PBS (and “Atomic Cover-up” coming this fall). He has written widely about the atomic bombings, and their aftermath, for over forty years.

Hiroshima: The Days After

President Truman's announcement to the nation on August 6, 1945--in which he carefully identified Hiroshima only as a "military base," not a large city--broke the news of both the invention of an atomic bomb and its first use in war, as I explored here two days ago. By that evening, radio commentators were weighing in with observations that often transcended Truman's announcement, suggesting that the public imagination was outrunning the official story. Contrasting emotions of gratification and anxiety had already emerged. H.V. Kaltenhorn warned, "We must assume that with the passage of only a little time, an improved form of the new weapon we use today can be turned against us."

It wasn't until the following morning, Aug. 7, that the government's press offensive appeared, with the first detailed account of the making of the atomic bomb, and the Hiroshima mission. Nearly every U.S. newspaper carried all or parts of 14 separate press releases distributed by the Pentagon several hours after the president's announcement. They carried headlines such as: "Atom Bombs Made in 3 Hidden Cities" and "New Age Ushered."

Many of them written by one man: W.L. Laurence, a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for the New York Times, "embedded" with the atomic project. General Leslie Groves, military director of the Manhattan Project, would later reflect, with satisfaction, that "most newspapers published our releases in their entirety. This is one of the few times since government releases have become so common that this has been done."

The Truman announcement of the atomic bombing on Aug. 6, 1945, and the flood of material from the War Department, firmly established the official nuclear narrative, which endures tro this day. It would not take long, however, for breaks in the official story to appear.

At first, journalists had to follow where the Pentagon led. Wartime censorship remained in effect, and there was no way any reporter could reach Hiroshima for a look around.

On Aug. 7, military officials confirmed that Hiroshima had been devastated: at least 60% of the city wiped off the map. They offered no casualty estimates, emphasizing instead that the obliterated area housed major industrial targets. (In fact, 80% of the casualties would be civilians, mainly women and children.) The Air Force provided the newspapers with an aerial photograph of Hiroshima. Significant targets were identified by name. For anyone paying close attention there was something troubling about this picture. Of the 30 targets, only four were specifically military in nature. "Industrial" sites consisted of three textile mills. (Indeed, a U.S. survey of the damage, not released to the press, found that residential areas bore the brunt of the bomb, with less than 10% of the city's manufacturing, transportation, and storage facilities damaged.)

On Guam, weaponeer William S. Parsons and Enola Gay pilot Paul Tibbets calmly answered reporters' questions, limiting their remarks to what they had observed after the bomb exploded. Asked how he felt about the people down below at the time of detonation, Parsons said that he experienced only relief that the bomb had worked and might be "worth so much in terms of shortening the war."

Almost without exception newspaper editorials endorsed the use of the bomb against Japan. Many of them sounded the theme of revenge (for Pearl Harbor) first raised in the Truman announcement. Most of them emphasized that using the bomb was merely the logical culmination of war. "However much we deplore the necessity," the Washington Post observed, "a struggle to the death commits all combatants to inflicting a maximum amount of destruction on the enemy within the shortest span of time." The Post added that it was "unreservedly glad that science put this new weapon at our disposal before the end of the war."

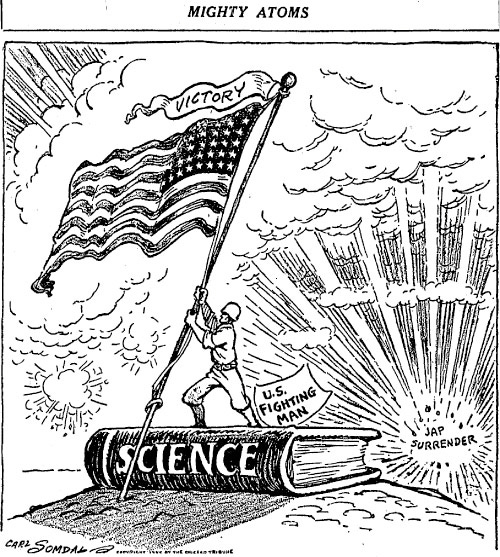

Referring to American leaders, the Chicago Tribune commented: "Being merciless, they were merciful." A drawing in the same newspaper pictured a dove of peace flying over Japan, an atomic bomb in its beak. Meanwhile, the unthinking atomic assembly line had rolled out another bomb, targeted on Kokura with Nagasaki as backup. No separate order was required or given by Truman.

American POWS Died in Hiroshima

The deaths have been known for awhile but the reports still shock most people. Few Americans know that among the tens of thousands victims in Hiroshima were at least a dozen and perhaps more American prisoners of war. They came from three bombers that had been shot down.

This was kept from the American people—even the families of the victims—for decades, along with so much else related to the atomic bombings.

One night, as a pair screamed in pain in their cells—asking to be put out of their misery—the other Americans asked the Japanese doctors to do something. “Do something?” one of the doctors replied. “You tell me what to do. You caused this.” The two men died later that night.

Three days after the Hiroshima blast, perhaps as many as a dozen Dutch POWs were killed in the bombing of Nagasaki. One American soldier there, a Navajo from New Mexico, survived in his cell.