More Notes After Seeing "Oppenheimer"

What happened at the other end of the bomb is missing...

Hello again on day five of this new bloggy newsletter on Oppenheimer: the man, the movie, The Bomb. As I’ve noted, I saw the movie at a screening in NYC on Saturday (and panel featuring director Christoper Nolan afterward). That night, I wrote up a few reflections, and posted even more yesterday. Now more today. This may go on the rest of the week. And you can subscribe, for free.

There’s a lot to unpack.

One thing that won’t get unpacked: the red carpet for tonight’s formerly gala premiere in NYC. No actors, no media…no carpet. By the way, I am doing interviews all week related to the Nolan movie and my book, so feel free to contact me if you are interested.

By the way, on this key date in 1945, Truman wrote in his diary about the coming Soviet declaration of war on Japan: “Fini Japs” when that happened (by mid-August). Yet he went ahead with his plans to drop atomic bombs over two Japanese cities. My piece here.

Before getting started: My latest article just out today at the great books-related site LitHub. It explores the odd fact that ultra-busy Oppenheimer, a few months after Hiroshima, found time to sit down twice with popular if oddball author Ayn Rand as she was researching her latest screenplay. This was for Paramount’s rival to the disturbing MGM movie that I explore in my book of the same name, “The Beginning or The End.” The Ayn Rand movie never got made (understandably, from my article) but Oppenheimer went on to lend his name to the horrid MGM film, which I covered last Friday in a major piece for Mother Jones.

Now onward to today. I’ve been offering these as rather brief notes on separate aspects of the challenging film, not a “review,” and will continue today. I will admit that, lost in some feelings of disappointment, one does need to pause and reflect that it’s still amazing that a three-hour movie raising questions about past and future use of The Bomb will be hitting multiplexes around the USA this weekend.

First the praise: As I’ve declared, the movie is brilliantly directed and acted and is a technical wonder (as you may have heard). Terrific script and sound design. Nolan should be roundly thanked for tackling this difficult, sensitive, important, subject. Great ending and message. Everyone should see it. And if I was an entertainment writer, I might say, “Cillian Murphy, meet Mr. Oscar!” But what about the content and emphasis?

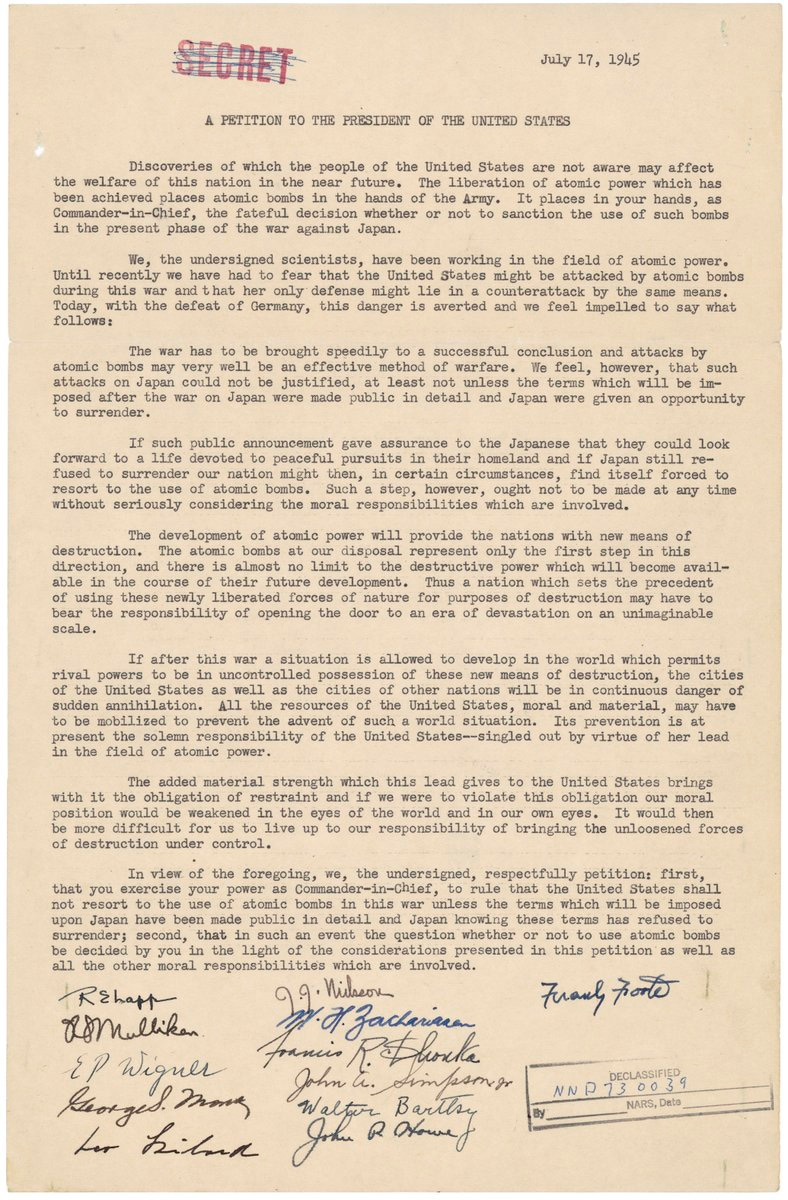

»»When I tweeted that I’d just seen the film, the first query I got from a nuclear expert, was, “Do they include the Szilard petition?” My answer was, yes, they do, and more than once. I wrote a whole piece about the petition but a little background here. Leo Szilard, a physicist and key contributor to the early bomb breakthroughs, came to oppose military use of of the weapon after Germany surrendered, and drew up and circulated a petition to Truman asking him to not order its use against cities in Japan, or at least delay awhile. He secured dozens of signatures at his Chicago lab and then it started gaining ground at other Manhattan Project sites.

In the new movie, Szilard ambushes Oppenheimer with the petition. Oppie gets flustered and accidentally (I think) knocks it out of the hands of a Szilard colleague. As in real life, Oppenheimer asserts that it is not a scientist’s role to get involved in such decisions—they have no special expertise in political or military issues. (Actually, he was helping the military in plans to drop the bomb, even providing its ideal detonation point for maximum destruction.) Later, he is approached by Edward Teller who says he is thinking of signing the petition—this will surprise some who know Teller only as guy who gave us the hydrogen bomb. Oppie urges him not to sign or circulate. And then there’s one more scene with Teller still pursuing and finally Oppenheimer convinces him to refrain. And this did happen pretty much like that in real-life.

The movie does omit Oppenheimer going even further in pretty much guaranteeing that the petition would not get to Truman until it was too late.

»» At about the three-quarter mark of the film—that is, 135 minutes--it looked to me like it was not going to even mention several key aspects of the decision to use the bomb, or its aftermath. Then, as if to cover all bases, many of them suddenly appear—albeit briefly and, in places, not very effectively. But there they are, which is something, if you can catch them flying by and, if a layperson, understand them.

So we suddenly learn, for example, in a single five-second snippet, that Oppenheimer, far from keeping his hands off the military use of the bomb, did take part in targeting decisions, including advocating that it aim to cause the most destruction over the center of a city. And we hear him say that the two bombs were used against an “essentially defeated” enemy. We witness, briefly and at a distance, an incident (well-known to some of us) where one of the Los Alamos scientists vomits in the bushes, as his colleagues party inside a lodge after Hiroshima. This really happened, the young man a critic of the bombing, but I’d guess many will assume the poor fellow just had too much to drink.

For the longest time, there is no mention of the Nagasaki bombing. This is nothing new, as long ago I dubbed it “The Forgotten Bomb.” But in the latter part of the movie, it suddenly gets cited three or four times, though always in an awkward, after-thought way. That’s better than nothing, but you’d never know that even many hardline historians who back the Hiroshima mission have strong qualms about Nagasaki—a kind of war crime—and we’d never know why from the movie. So consult my article here. (I didn’t write the headline but it is apt: “America Killed 90,000 People for No Good Reason, and Then Just Forgot About It.” ) The downplaying of Nagasaki in the movie is surprising in that, in real life, it was the emerging death toll from the second bomb that sparked Oppenheimer’s regrets about the military use of the bomb.

The man most responsible for the unnecessary 75,000 civilian deaths there, General Groves—a rather sympathetic Matt Damon in the movie—gets a complete pass, as he does in several other key areas, such as his strenuous and effective efforts to cover up, with Oppie’s help, radiation hazards connected with the new weapon.

Well, Hollywood has made some progress. In the first atomic movie, from MGM, that I explore in my book, Nagasaki was not even mentioned once!

»>Then there’s this: I warned awhile ago that it looked like in the movie there would be no images of what happened at the other end of the bomb in Japan, as both the U.S. and Brit ratings boards did not cite violence or graphic content in handing out their “R” symbols (but yes, there is a bit of nudity, the usual female breasts). And, indeed, the movie does not deliver any of that.

After Oppie is informed that Hiroshima has been bombed, his fellow scientists cheer and chant his name, and he reluctantly, then happily, celebrates in a brief address at Los Alamos, all accurate. He even comes to claim that the Japanese are not feeling too good right about then! Then he starts to tremble a bit and see visions (as he does elsewhere in the movie). He very briefly imagines a young woman with a partly burned or melted race. Amazingly, Nolan cast his own daughter in this role.

Staggering now, Oppie seems to step in a black mass on the floor about the size of a basketball. When he lifts his shoe some of the black covers it. Now, this is handled so unclearly—there is much racket and vibrations (he is having a vision)—that I had to ask my wife later if my interpretation was correct: that this was supposed to represent a charred Japanese body. I’m still not sure of that. Like some of the other very good references in the movie (audio or visual), it goes by too quickly and, I’d imagine, hard for even someone experienced in nuclear imagery to identify. Perhaps if the black mass was more elongated, you know, the shape of a human body, that might have helped. Or maybe it is just supposed to represent a black heart or black soul.

The only other coverage of what might happened on the ground in Japan, as I recall, comes in another short scene where Oppenheimer, in what we assume is a Los Alamos or military screening room, stares ahead at some footage, which we don’t see, and betrays a bit of emotion, as a narrator refers to what we have to guess is a scene of death and destruction in one of Japan’s atomic cities. We only see Oppie from the side, with no shot of the screen. And this ends quickly.

And that’s it for a visit to the other end of the bomb.

What the movie audience will miss? For one thing, below, my award-winning 2021 film…more tomorrow…

The Szilard petition:

Looking forward to seeing this.

Really hits close to home. Seen many lives destroy by people trying to do "the right thing" only to wake up to the realization they were unknowingly aiding and abetting the war machine.

Thank-you for covering this topic!

I think the film Oppenheimer is not a well made film as you say it is. The last third is structured as a feeble Melodrama with a real petty villain and an ineffective goody. So there is no Griffithian last minute rescue in this Melodrama. I don't know what criteria you use Greg to criticise the film thematically, as you rightly do, and still maintain its artistic 'brilliance'. I have written to show how exactly it is constructed and its weakness but you are not interested in that approach which is sad.