My First August 6th in Hiroshima

Private and public ceremonies, a bell tolls as cicadas cry, lanterns in the river, but were the souls consoled?

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including “Hiroshima in America,” “Atomic Cover-up,” and the recent award-winning “The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood—and America—Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.” He has directed three documentary films since 2021 for PBS. He has written about the atomic bombings for over forty years. You can subscribe to this newsletter, or his one devoted to music and politics, for free. UPDATE: My 2022 film “Atomic Cover-up” available today for anyone with a library card via Kanopy.

>From a few years back, but little has changed, except nearly all of the bomb survivors, the “hibakusha,” have now passed away (but their children and other descendants continue to bear witness). All photos: my own, taken on that August day.

On the evening of August 5 we were told we ought to retire early and get up before five the next morning if we wanted to truly appreciate the occasion, before the TV cameras and the politicians horned in. August 6 is not like any other day in Hiroshima. It is not like any other day anywhere. What other city even has such a day to commemorate? More died in the siege of Leningrad, but the carnage occurred over many months. More died in the Holocaust, but the victims were separated by the miles between the death camps.

What city suffered so on a single day? Hiroshima was the world’s first sixty-second massacre, and the city can even mark the moment it met its fate: 8:15 a.m. Before the clock ticked again, thousands had been slain, and the dying had only begun. This is just one lesson illuminated on August 6 in Hiroshima, and only in Hiroshima on August 6.

They began arriving before dawn. With the glow of a torch the only light in the Peace Park, the first pilgrims paid their respects at the memorial cenotaph. Some had driven for hours to get there and after twenty minutes they will drive home. Young couples, infants in tow, grieve for grandparents, aunts, and uncles, standing silent (even the children) in the dark, heads bowed, before the cenotaph. Few lingered, almost no one wept. Buddhists dressed in white smocks sat just to the left of the monument, chanting and beating small drums. In front of them rested a long table bearing fruit, flowers, cigarettes, liquor -- comfort for the dead. It could be almost any century, any occasion of mass mourning.

The sky brightened. Television cameramen with klieg lights arrived in force. Peering under the arches of the cenotaph one could see the faint outline of the A-Bomb Dome and its famous skeletal crown which lost its copper skin on August 6, 1945. What dome is this that can not reflect the rising sun? Through which one can see the sky turning blue?

Nearby, on the Aioi Bridge, automobile traffic was sparse. Joggers commanded the road. At this hour on “that day” the Enola Gay was well on its way, this bridge its target. Along the river it was quiet. A crane, not of the paper variety, sat idly atop a new office tower. Hiroshima, no longer rebuilding — just building. The sun was rising on August 6.

Over at the Memorial Mound, home to the ashes of 70,000 victims of the bomb, several dozen Buddhist, Shinto, Protestant and Catholic priests conducted a solemn ceremony. The smell of incense, so evocative of the sweet smoke from a funeral pyre—especially at this spot—was almost suffocating. Several of the Shinto priests wiped away tears.

More than 40,000 people, including hundreds of foreigners, attended the official peace ceremony, which to this day takes place on the broad lawn between the cenotaph and the Peace Museum, often in sweltering heat. The ceremony never wavers. Men and women dressed in black carry to the cenotaph, in wooden buckets, water drawn from Hiroshima’s seven rivers, where so many perished seeking safety. (Many who could not reach a river died thirsty — crying for water.) Then the names of hibakusha who have passed away, possibly from lingering effects of the bomb, in the past year were presented at the cenotaph, where they will be lodged forever. Many, in this way, are finally re-united with their parents.

Suddenly it was 8:15. In thousands of homes across Japan the bereaved knelt in front of family altars. In Hiroshima street cars stopped and children paused on sidewalks and bowed their heads. Factory workers put down their tools. The haunting buzzing of the cicadas sounded like high-pitched cries. A centuries-old bell rang deeply, like a distant rumble. This was all the time the bomb needed to do its work.

So this is what it was like on that day: A cloudless sky, oppressive heat, and the sun just so. The impressive profile of new buildings and the survival of the human spirit in Hiroshima offer little comfort on August 6.

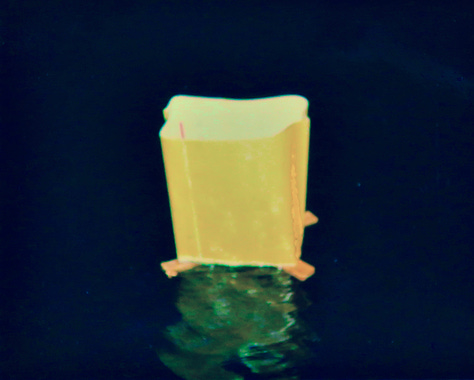

At dusk every year on this day, relatives and friends of the deceased come to the Peace Park for the Paper Lantern Ceremony. For a few yen they purchase wooden sticks, sheets of red, yellow, green or blue paper, and plastic tubes. With this material they construct a foot-high lantern, write the name of a victim on the side, place a thin, white candle in the center, light it, and carry it down one of the stairways leading to the river. Teenagers take the lanterns, wade a few yards into the river, and launch them on their way, with the tide running out.

Thousands gather on the bridges in the dark to quietly watch the souls of the dead consoled by water. On rivers where countless bodies once floated in an undulating mass grave, paper lanterns bob and weave as far as the eye can see. Some float alone, others bunch in small groups, like a family or classmates (you can’t help imagining this). I rented a rowboat and spent a few somber minutes among them. With neon flames dancing, the lanterns rock on the river in the dark. As the lights flicker out, the current carries them past the Peace Park to the sea.

This is the anonymity of mass death made manifest. Each lantern represents an individual who, at fifteen minutes past eight on the morning of this day in 1945, was seething with life, and at 8:16 was dead, or dying. Among those watching this ritual are hibakusha who know that paper lanterns with their names written on them will be floating on the same river some day.

That night, about 2:30, a substantial earthquake rocked our hotel, sending many of us rushing downstairs to the lobby. Perhaps the souls on the river were not consoled, after all.

»>Just published: an expanded edition of my book Atomic Cover-up, now with several thousand words of mine re: the movie and the man Oppenheimer. And it’s on sale this week as an ebook for just $3.99 ($12.95 for the paperback).

Keep it up. Incredible stuff.