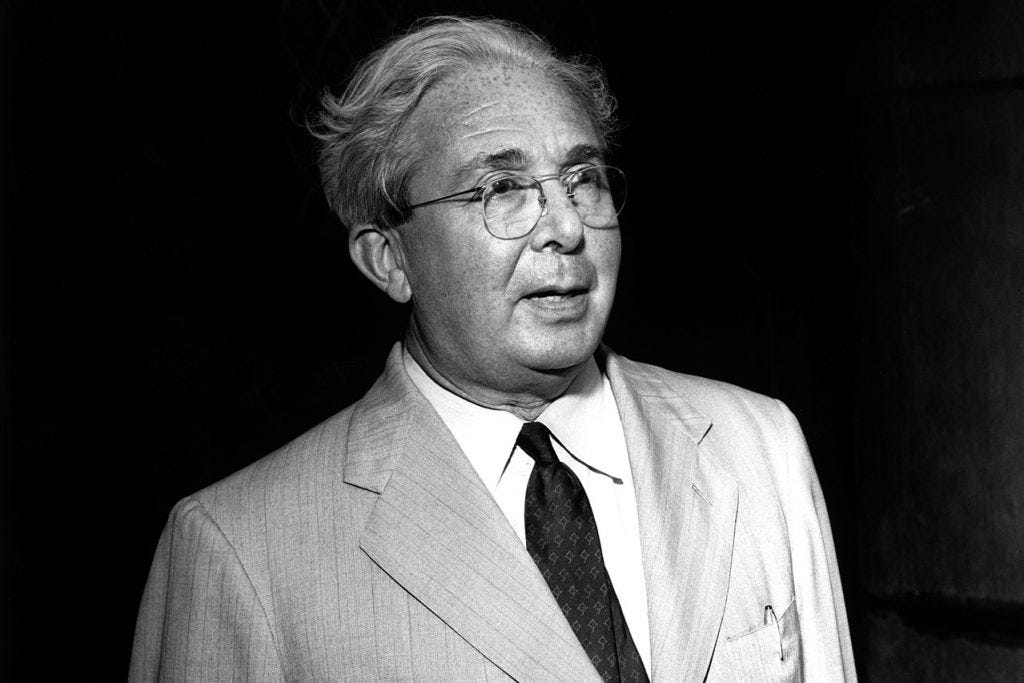

On July 4, 1945: The Man Who Tried to Halt the Atomic Bombings

Famed physicist Leo Szilard sent a petition to Truman. General Groves stopped it.

Greg Mitchell is the author of more than a dozen books and now writer/director of award-winning films aired via PBS, including “Atomic Cover-up” and “Memorial Day Massacre.” Now watch trailer for acclaimed 2025 film “The Atomic Bowl” coming to PBS in July. You can still subscribe to this newsletter for FREE. Sustain this newsletter by ordering the companion book to “The Atomic Bowl.”

On July 4, 1945, the great atomic scientist Leo Szilard finished a letter that would become the strongest (and one of the very few) real attempts at halting President Truman's march to using the atomic bomb--which was two weeks from its first test at Trinity--against Japanese cities.

It’s well known that as the Truman White House made plans to use the first atomic bombs against Japan in the summer of 1945, a large group of atomic scientists, many of whom had worked on the bomb project, raised their voices, or at least their names, in protest. They were led by the Szilard. On July 3, he finished a petition to the president for his fellow scientists to consider, which called atomic bombs “a means for the ruthless annihilation of cities.” It asked the president “to rule that the United States shall not, in the present phase of the war, resort to the use of atomic bombs.”

The following day, July 4, he wrote this cover letter (below). The same day, Leslie Groves, military chief of the Manhattan Project, wrote Winston Churchill’s science advisor seeking advice on how to combat Szilard and his colleagues. The FBI was already following Szilard. The bomb would be dropped over Hiroshima on August 6.

July 4, 1945

Dear _______________

Enclosed is the text of a petition which will be submitted to the President of the United States. As you will see, this petition is based on purely moral considerations.

It may very well be that the decision of the President whether or not to use atomic bombs in the war against Japan will largely be based on considerations of expediency. On the basis of expediency, many arguments could be put forward both for and against our use of atomic bombs against Japan.

Such arguments could be considered only within the framework of a thorough analysis of the situation which will face the United States after this war and it was felt that no useful purpose would be served by considering arguments of expediency in a short petition.

However small the chance might be that our petition may influence the course of events, I personally feel that it would be a matter of importance if a large number of scientists who have worked in this field went clearly and unmistakably on record as to their opposition on moral grounds to the use of these bombs in the present phase of the war.

Many of us are inclined to say that individual Germans share the guilt for the acts which Germany committed during this war because they did not raise their voices in protest against these acts. Their defense that their protest would have been of no avail hardly seems acceptable even though these Germans could not have protests without running risks to life and liberty. We are in a position to raise our voices without incurring any such risks even though we might incur the displeasure of some of those who are at present in charge of controlling the work on “atomic power”.

The fact that the people of the people of the United States are unaware of the choice which faces us increases our responsibility in this matter since those who have worked on “atomic power” represent a sample of the population and they alone are in a position to form an opinion and declare their stand.

Anyone who might wish to go on record by signing the petition ought to have an opportunity to do so and, therefore, it would be appreciated if you could give every member of your group an opportunity for signing.

Leo Szilard

What happened next? Well, the petition gained from than 180 signatures—Oppenheimer obviously not one, and actively discouraged others—but was then delayed in getting to President Truman by Gen. Leslie Groves, military head of the Manhattan Project, until the A-bombs were ready to use, in early August. Groves also commissioned a poll of atomic scientists, which found that over 80% favored a demonstration shot only--so he squelched that, too. Much more in my 2020 book: The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood--and America--Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

I’ve mentioned previously that my new award-winning film will start streaming, and screening on TV, from PBS on July 12. This week the companion e-book with the same title has been published: “The Atomic Bowl: Football at Ground Zero—and Nuclear Peril Today.” It’s just $5.79 and includes previously unpublished stills and material from the film and much more. Read more here. Thanks.