One Magazine, Two Profound Warnings on Nuclear Weapons Today

The Atlantic is marking the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombings in a vital way.

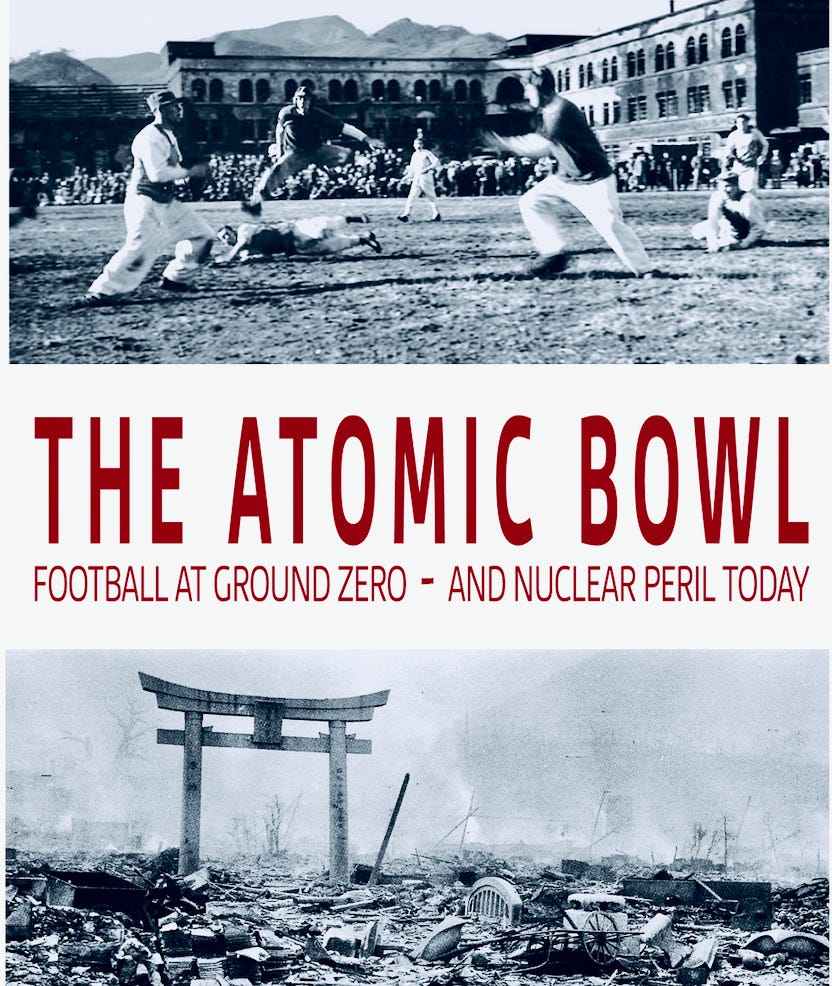

Greg Mitchell is the author of more than a dozen books and now writer/director of three award-winning films aired via PBS, including “Atomic Cover-up” and “Memorial Day Massacre.” Now watch trailer for acclaimed 2025 film “The Atomic Bowl” coming to PBS in July. You can still subscribe to this newsletter for FREE. Sustain this newsletter by ordering one of his books.

Just a quick one here to direct you to a pair of articles.

As you may know, I have been writing about and directing films about the atomic bombings of Japan for over four decades. Coverage by others in the media waxes and wanes, with major coverage only during prime “anniversary years.” The 50th in 1995 really drew a lot of attention, the 75th less so but still fairly broad.

I’m not sure what I expected for this year, the 80th. It’s true that I directed another film, mainly about the forgotten Nagasaki bomb, the aftermath and lessons for today, The Atomic Bowl, to coincide with it. And I will urge anyone out there who writes about films or nuclear or related issues to contact me if you wish to view it or talk to me before it starts streaming via PBS on July 12. But still, I really didn’t have a lot of confidence that “80” was enough of a catchy number for profound media coverage on the significance of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki for 2025 and beyond.

Well, The Atlantic magazine, one of the best outlets today for sure, seems to be setting a much-needed urgent tone.

Online this week, and apparently in the next print issue, are two excellent lengthy pieces. One by staff writer Tom Nichols, the other by editor Jeffrey Goldberg. You can follow the links below but these days, of course, there is a pay wall you may have to negotiate. But just a couple of excerpts to get you started, and thanks again to my wife for drawing my attention to them. (Illustration at the top by Michael Haddad.)

From the Nichols piece:

Human survival depends on an imperfect system working perfectly. Command and control relies on technology that must always function and heads that must always stay cool. Some defense analysts wonder if AI—which reacts faster and more dispassionately to information than human beings—could alleviate some of the burden of nuclear decision making. This is a spectacularly dangerous idea. AI might be helpful in rapidly sorting data, and in distinguishing a real attack from an error, but it is not infallible. The president doesn’t need instantaneous decisions from an algorithm.

Vesting sole authority in the president is perhaps the least worst option when it comes to deterring a major attack. In a time crunch, groupthink can be as dangerous as the frenzied judgment of one person, and retaliatory orders must remain the president’s decision—above any bureaucracy, and separate from the military and its war games. The choice to strike first, however, should be a political debate. The president should not have the option to start a nuclear war by himself.

But what happens when a president with poor judgment or few morals arrives in the White House, or when a president deteriorates in office? Today, the only immediate checks on a reckless president are the human beings in the chain of command, who would have to choose to abdicate their duties in order to stall or thwart an order they found reprehensible or insane. Members of the military, however, are trained to obey and execute; mutiny is not a fail-safe device. The president could fire and replace anyone who impedes the process. And U.S. service members should never be put in a position to stop orders that defy reason; gaming out such a scenario is corrosive to national security and American democracy itself.

When I asked a former Air Force missile-squadron commander if senior officers could refuse the order to launch nuclear weapons, he said: “We were told we can refuse illegal and immoral orders.” He paused. “But no one ever told us what immoral means.”

And from Goldberg:

As a species, we are not particularly skilled at making time-pressured, closely reasoned decisions about matters of life and death. The sociobiologist E. O. Wilson described the central problem of humanity this way: ‘We have Paleolithic emotions, medieval institutions, and godlike technology.’ The main challenge of the 80 years since the Trinity atomic test has been that we do not possess the cognitive, spiritual, and emotional capabilities necessary to successfully manage nuclear weapons without the risk of catastrophic failure….

Trump remains an unstable leader in a world far more unstable than it was during his first term. No president has ever been anything close to a perfect steward of America’s national security and its nuclear arsenal, but Trump is less qualified than almost any previous leader to manage a nuclear crisis. (Only the late-stage, frequently inebriated Richard Nixon was arguably more dangerous.) Trump is highly reactive, sensitive to insult, and incurious.

It is unfair to say that he is likely to wake up one morning and decide to use nuclear weapons—he has spoken intermittently about his loathing of such weapons, and of war more generally—but he could very easily mismanage his way, again, into an escalatory spiral.

And he points out: “We are living through one of the more febrile periods of the nuclear era.”

We should honestly recognize that 80 years of analytic writings by experts, however informed and articulate, has not brought us any closer to nuclear salvation. In fact, the situation is more dangerous than it's ever been. This is not because the analysis is poor, but rather because reason is the wrong channel on which to approach topics of this scale.

The nuclear weapons threat will be resolved the way so many of our human problems are addressed, through pain. Sooner or later there will be the next detonation(s), whether with intent or by mistake. Our best hope is that this event will be large enough to scare us in to sanity, and small enough to allow for a change of course.

A nuclear weapons accident would be the ideal event, given that it wouldn't result in a war.