Oppenheimer and Bikini--on 78th Anniversary

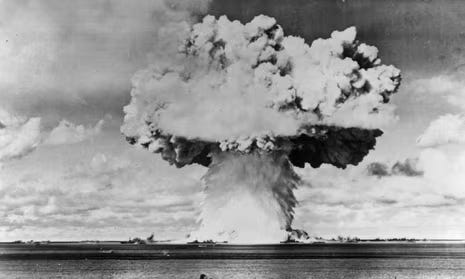

The first atomic test in the Pacific revealed so much and began decades of nuclear explosions that would damage so many.

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including “Hiroshima in America,” “Atomic Cover-up,” and “The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood—and America—Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.” He has directed three documentary films since 2021, including three for PBS (one of them the award-winning “Atomic Cover-up”). You can still subscribe to this newsletter for free.

The Christopher Nolan movie, and many others, focused far more attention on the first atomic test at the Trinity site in July 1945 than on the results of the Hiroshima bombing three weeks later (and even less re: poor Nagasaki). And what about the first postwar test? That came on July 1, 1946, in the Bikini Atoll, following the forced removal of all 167 of its tribal residents.

J. Robert Oppenheimer had decided not to play the role of distinguished eyewitness. He had seen more than enough at Trinity.

That first larger-than-Hiroshima-sized bomb at Bikini was set off above a fleet of antiquated ships, testing its power at sea. This was not without controversy. Few in the media cared what happened to the Bikinian natives, but some worried the blast might ignite the atmosphere, trigger tidal waves, or create a fissure in the earth’s crust. Newspapers carried witty accounts of Los Angeles residents planning to enjoy picnics high in the hills on the day of the blast instead of by the beach in case a tsunami rose from the ocean.

Oppenheimer had explained in a message to Truman that he had severe “misgivings” about the tests, which were shared by many other scientists. If the purpose of the test was to judge how vessels might survive—well, no such blast was needed: “If an atomic bomb comes close enough to a ship . . . it will sink it.” For just one percent of the projected $100 million cost for the tests “one could obtain more useful information.” As for the radiation studies: they, too, could be obtained more accurately and cheaply in a lab. And why a “trivial” test at sea? Everyone knew the purpose of the new weapon (as the world had already been shown, by Truman himself) “lies in their use for the bombardment of cities.” Most importantly, Oppenheimer questioned “the appropriateness of a purely military test of atomic weapons, at a time when our plans for effectively eliminating them from national armaments are in their earliest beginnings.”

Truman was not swayed. He forwarded the letter to Acting Secretary of State Acheson, reminding him that this was the same “crybaby scientist” who claimed he had blood on his hands when they met in the Oval Office the previous October (as shown in Nolan’s movie). “I think he has concocted himself an alibi in this letter,” Truman decided.

And what about the islanders? Besides covering the sabotage of the first movie on the making and use of the bomb (from MGM) by the Truman White House and military, my book The Beginning or the End covers other nuclear-related events of that crucial year of 1946. Among the most important: the beginning of the U.S. nuclear blasts in the Pacific. Here is an excerpt on evil plans for moving natives of Bikini to a far harsher new home. They would never return home.

The U.S. had asked the 167 inhabitants of the Bikini atoll (made up of some 23 tiny islands) in Micronesia to "temporarily" relocate so that America could set up new and devastatingly powerful weapons for "the good of mankind and to end all world wars." The first test was planned for late spring or early summer. It called for a weapon exceeding 21 kilotons in force (where the Hiroshima blast was 15 kilotons) to be dropped over dozens of unoccupied junked ships in the Bikini lagoon to judge the effects on that fleet. The second test would be set off in the same area under water, beneath another ghost fleet, by remote control.

The Bikini islanders learned of their forced evacuation when Navy Commodore Ben Wyatt, military governor of the Marshall Islands, arrived to remind them of Biblical passages--they had long welcomed Protestant missionaries--comparing them to "the children of Israel whom the Lord saved from their enemy and led into the Promised Land."

The Bikinians were none too pleased with this notion, but their leader, King Juda finally agreed to the relocation request, announcing "We will go, believing that everything is in the hands of God." (Wyatt staged a re-enactment of this meeting for a newsreel but it required seven re-takes because King Juda failed to act enthusiastic enough.) Of the eleven heads of extended Bikini families, nine chose Rongerik, 125 miles to the east--about one-sixth the size of their current island--as their temporary home.

In reality, Wyatt and other U.S. officials knew that the islanders would never be allowed to return to what was certain to be a heavily-contaminated former paradise. Time magazine quoted a U.S. officer as boasting that easing the Bikinians out was "one hell of a good sales job." The magazine writer added: "Progress chuckled over a victory." Time observed that they took few possessions with them beyond their bibles, hymnals and furniture brought by missionaries, along with "latent syphilis left by Yankee whalers of the pre-atomic age."

No one lived on Rongerik, which was helpful, but the reason for that was not: It had few supplies of food and fresh water. The Navy knew of the challenges the Bikinians would face there, but still left them with only a few weeks of water and food.

Film on the test and tragedy of the offloaded islanders:

*

Oppenheimer and Gaza https://open.substack.com/pub/hankkalet/p/the-nazi-effect?r=biwh5&utm_medium=ios