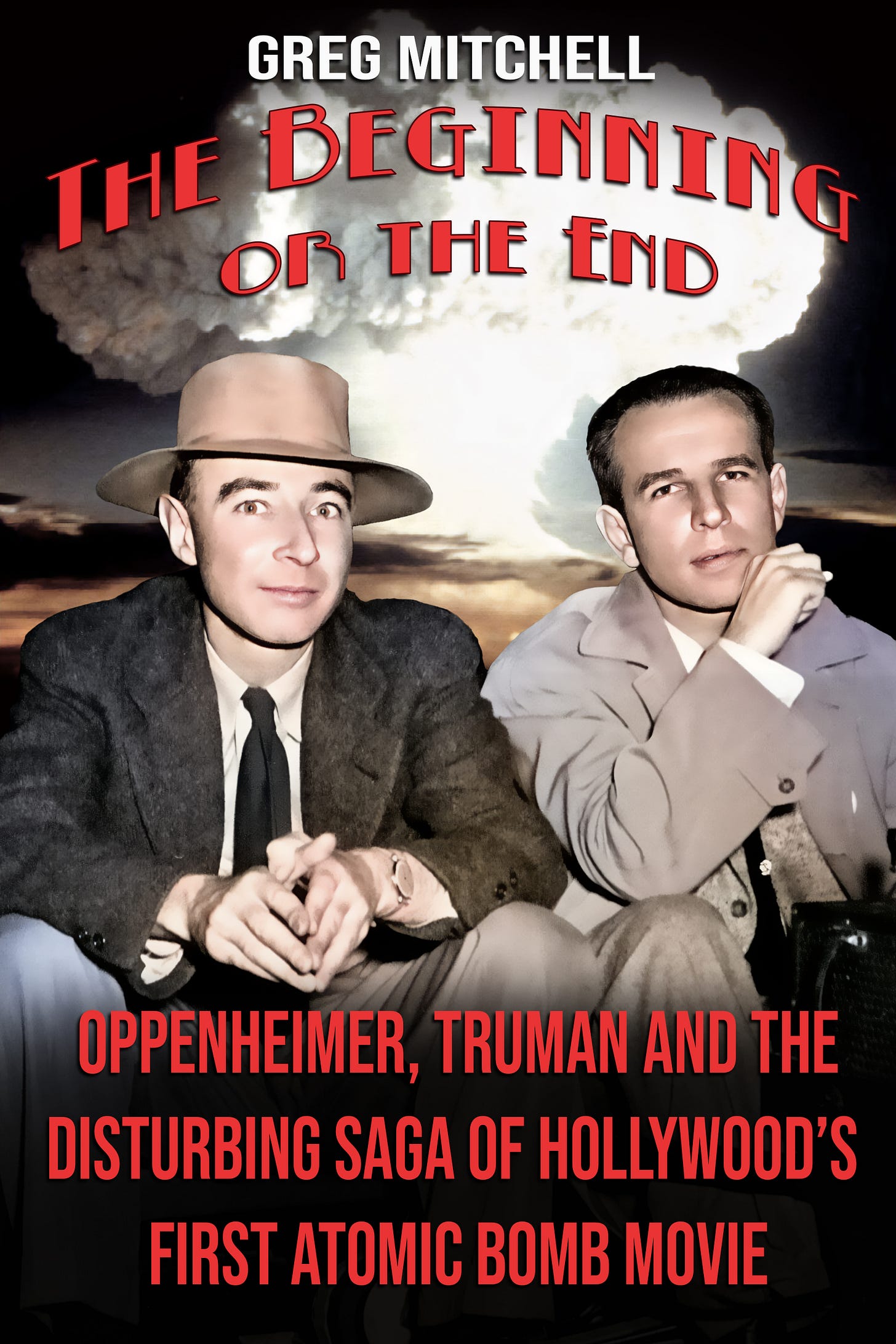

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including “Hiroshima in America,” “Atomic Cover-up,” and the recent award-winning“The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood—and America—Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb,” and has directed three documentary films since 2021, including two for PBS (plus award-winning “Atomic Cover-up”). He has written widely about the atomic bomb and atomic bombings, and their aftermath, for over forty years.

Vintage 1950 editorial cartoon, above. Oppenheimer turns on the physicist raising objections to the “Super.”

Welcome to Week 3 of this newsletter, as subscriptions continue to surge, thank you. I completed a round of a dozen or more radio and podcast interviews yesterday (a couple here and here). Whatever one thinks of flaws in the Nolan movie, it has certainly sparked interest in the atomic/nuclear subject and now we’ll see where that leads, if anywhere. My books Atomic Cover-up and The Beginning or the End have also drawn new attention, adding their messages to the current debate.

On the other hand, we have reached that point of Oppie cultural mania that tends to detract from consideration of deeper issues. This occurred in the months after Hiroshima, as well, with all things Atomic, when public fears about the new weapon (one day it could land on us) ran rampant and humor or absurdity helped mitigate that. So I tried to laugh yesterday when multiple outlets, including the Washington Post, posted lengthy pieces about….Oppie’s famous martinis and recipes for same.

Now, I knew about his reputation as a mover and shaker (not stirred) in that regard from my research long ago, though I must say that just as many people seemed to call them “awful” as wonderful. Basically they are just gin “bombs” with barely a splash of vermouth—so you might quickly get Oppie-hammered—with the twist that the rim of the glass is then dipped in a lime/honey mix, and then, like Lewis Strauss’s revenge, it is served very cold. Here from the Post:

Nolan incorporated the drink in a pivotal scene, though it isn’t explicitly referenced or explained. Oppenheimer, played by Cillian Murphy, is in the kitchen during a dinner party with his friend and Berkeley colleague Haakon Chevalier when he prepares several glasses. Their conversation — in which Chevalier suggests a means of passing along information about his work to the Russians — later becomes known as the “Chevalier Incident,” and Oppenheimer’s attempt to obscure his friend’s identity becomes problematic. The conversation in the scene is so gripping viewers might very well miss the action. And if they do notice it, they might wonder why the heck he’s dipping coupe glasses into a little bowl of what looks like dark liquid.

His wife, Kitty, played by Emily Blunt, ends the men’s exchange when she arrives to deliver a line that underscores both her fondness for drinks and indifference to motherhood: “The brat is down,” she says. “Where are the martinis?”

It sounded better than what many other workers at Los Alamos regularly consumed during the time working on the bomb. The bachelors among them often hosted parties where the drink was “a concoction of half lab alcohol and half grapefruit juice mixed in a 32-gallon G.I. can and chilled with a chunk of smoking dry ice,” according to “American Prometheus.”

So here’s one of those early “atomic craze” popular songs from late-1945, “Atomic Cocktail,” by Slim Gaillard.

The Hiroshima bomb killed several American POWs on August 6, 1945 (more on this down the road). But the first recorded American to die after this cataclysm was a nuclear scientist back in the U.S. named Harry Daghlian. Just days after Nagasaki was attacked, he was involved in a nuclear experiment at Los Alamos that went awry, and died one month later. The Roland Joffe film Fat Man and Little Boy showed a kind of version of the accident, starring John Cusack.

I’ve written here a lot about how the Nolan film pretty much ignores the radiation angle of Oppie’s new weapon, right from the Trinity test and after-effects on downwinders—and how this established the twin, long enduring, postwar legacy of lethality + secrecy.

On September 21, 1945, the New York Times published a brief item headlined “Atomic Bomb Worker Died From Burns.” Officials at Los Alamos, revealed that six days earlier a “worker” had died “from burns in an industrial accident.” Daghlian, age 24, identified only as an instructor at Purdue University who had joined the bomb project in November 1943.

That was it. There was no information about the nature of the “industrial accident,” when it had occurred, or why the fatality was being reported five days after the fact. This wire service report would be the only mention of the incident in the American media. Only years later would details of the accident emerge. Daghlian was, in fact, no mere industrial “worker” but a scientist intimately involved with the bomb project. He had even helped assemble the core of the Trinity bomb.

Less than a year after Harry Daghlian died, Los Alamos witnessed a second fatal accident during a criticality experiment gone wrong. This was the brilliant Canadian native Louis Slotin (above), age thirty-five, who had helped arm the Hiroshima bomb and then the core slated to be used in the first Bikini blast, which he had planned to witness.

Enrico Fermi had warned Slotin months earlier that if he continued his risky criticality experiments--known as "tickling the tiger's tail"--he would be dead within a year. Unlike the solo Daghlian accident, this time eight Los Alamos personnel were exposed to the radiation, with Slotin getting far the worst of it. As Slotin lingered near-death for days, the government planned to avoid citing radiation as the culprit in any public statements--just as it had done after the Daghlian tragedy. Then his friend, the physicist Philip Morrison (who had witnessed even worse in Hiroshima), insisted on an honest reckoning.

In the MGM movie The Beginning or the End, Matt Cochran would die within a day (to fit the horrid film’s time frame), while Slotin would experience nine days of suffering; the others exposed would survive. When his passing was announced, Slotin was commonly referred to as "the first peacetime victim" of radiation from the bomb project. To balance the horrors of what nuclear accidents might mean for the future, officials played up the "hero" angle--how Slotin had maybe saved the others by sacrificing himself, reaching in and separating components to halt the runaway atoms. General Groves had written a note to him before he died hailing his "heroic actions" and dispatched a military plane to bring his parents to his bedside.

The Time headline called him "Hero of Los Alamos" but admitted that radiation releases "may become a familiar factor in the atomic age."

Song of the Day

Maybe a little off topic, but here’s an impromptu, stirring rendition of Dylan’s “Times They Are A-changin” by Sinead O’Connor. Are they, in the nuclear world, at last?