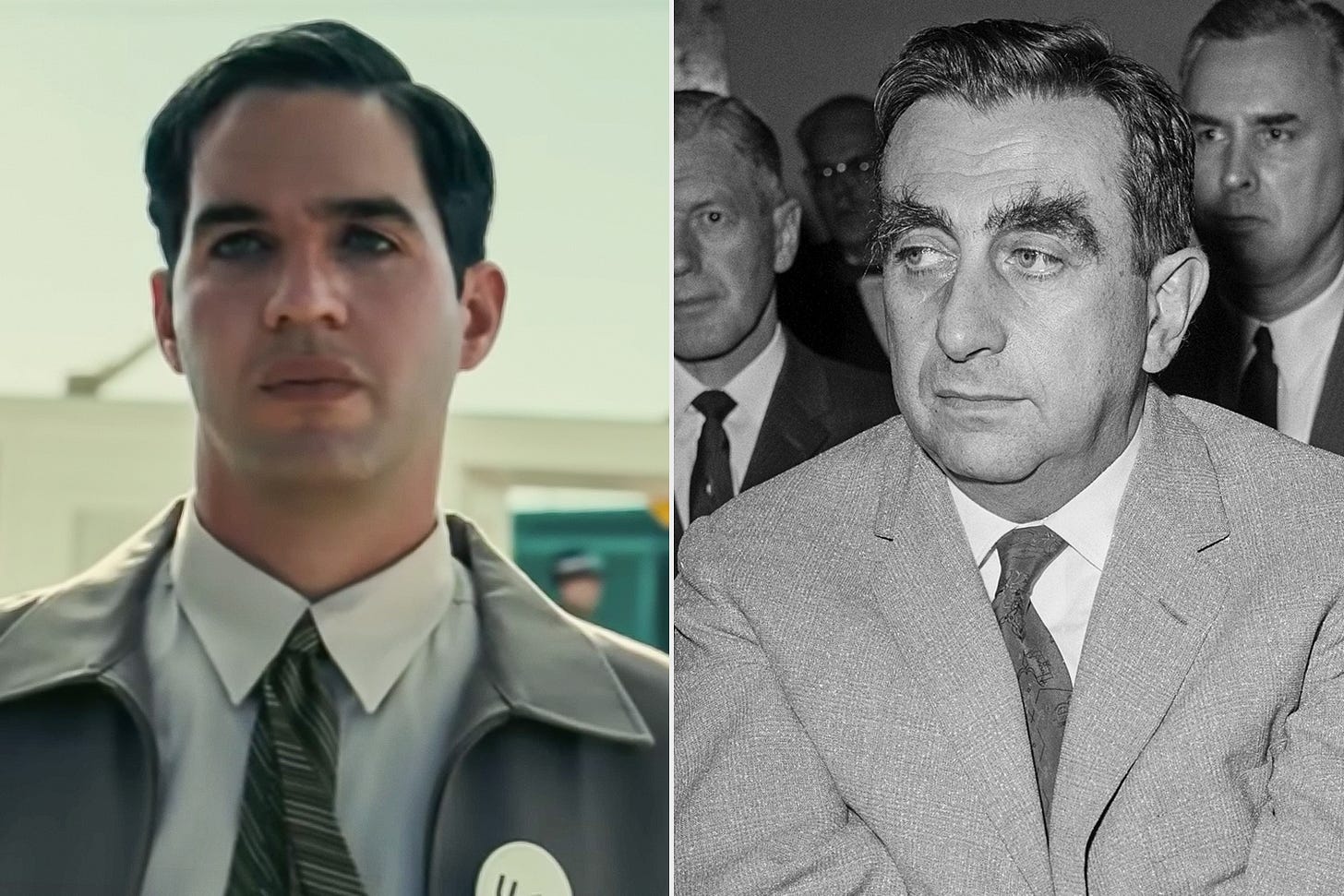

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including “Hiroshima in America,” “Atomic Cover-up,” and the recent award-winning “The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood—and America—Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.” He has directed three documentary films since 2021, two of which have aired over PBS (and “Atomic Cover-up” coming this fall). He has written widely about the atomic bombings, and their aftermath, for over forty years.

On this date in 1945, the day after the the Nagasaki bomb:

MEMORANDUM TO: Chief of Staff.

The next bomb of the implosion type had been scheduled to be ready for delivery on the target on the first good weather after 24 August 1945. We have gained 4 days in manufacture and expect to ship from New Mexico on 12 or 13 August the final components. Providing there are no unforeseen difficulties in manufacture, in transportation to the theatre or after arrival in the theatre, the bomb should be ready for delivery on the first suitable weather after 17 or 18 August.

L. R. Groves,

Major General, USA

Henry Wallace, Secretary of Commerce under Truman, noted the events of the August 10, 1945 cabinet meeting in his diary.

Truman said he had given orders to stop atomic bombing. He said the thought of wiping out another 100,000 people was too horrible. He didn’t like the idea of killing, as he said, “all those kids.”

The great Charles P. Pierce over at Esquire quotes extensively from my article at Mother Jones yesterday on Nagasaki, then adds:

In his book, Bomb Power, historian Garry Wills quotes a letter signed by several scientists who had worked on the Manhattan Project, who warned against the production of the "Super," Edward Teller's beloved hydrogen bomb. In part, the letter reads, “Necessarily, such a weapon goes beyond any military objective and ends in the range of very great natural catastrophes. By its very nature it cannot be confined to a military objective but becomes a weapon which in practical effect is almost one of genocide.”

The 78 years since Bock's Car materialized in the sky over Nagasaki have rendered its mission that day a source of unspoken shame. The country has worked very hard to erase the fact that it wiped out a city and killed 100,000 people for no conceivable military purpose at the end of a war that already had been won. The only thing it demonstrated to the Soviets was that the United States could be as inexplicably bloodthirsty as any other nation-state since the beginning of time.

Oppenheimer’s Bomb Followed Him Home

And finally, the story of a very special hibakusha—or atomic bomb survivor—who I met in Nagasaki, a saga too terrible to be true, but true nevertheless, adapted from my book Atomic Cover-up:

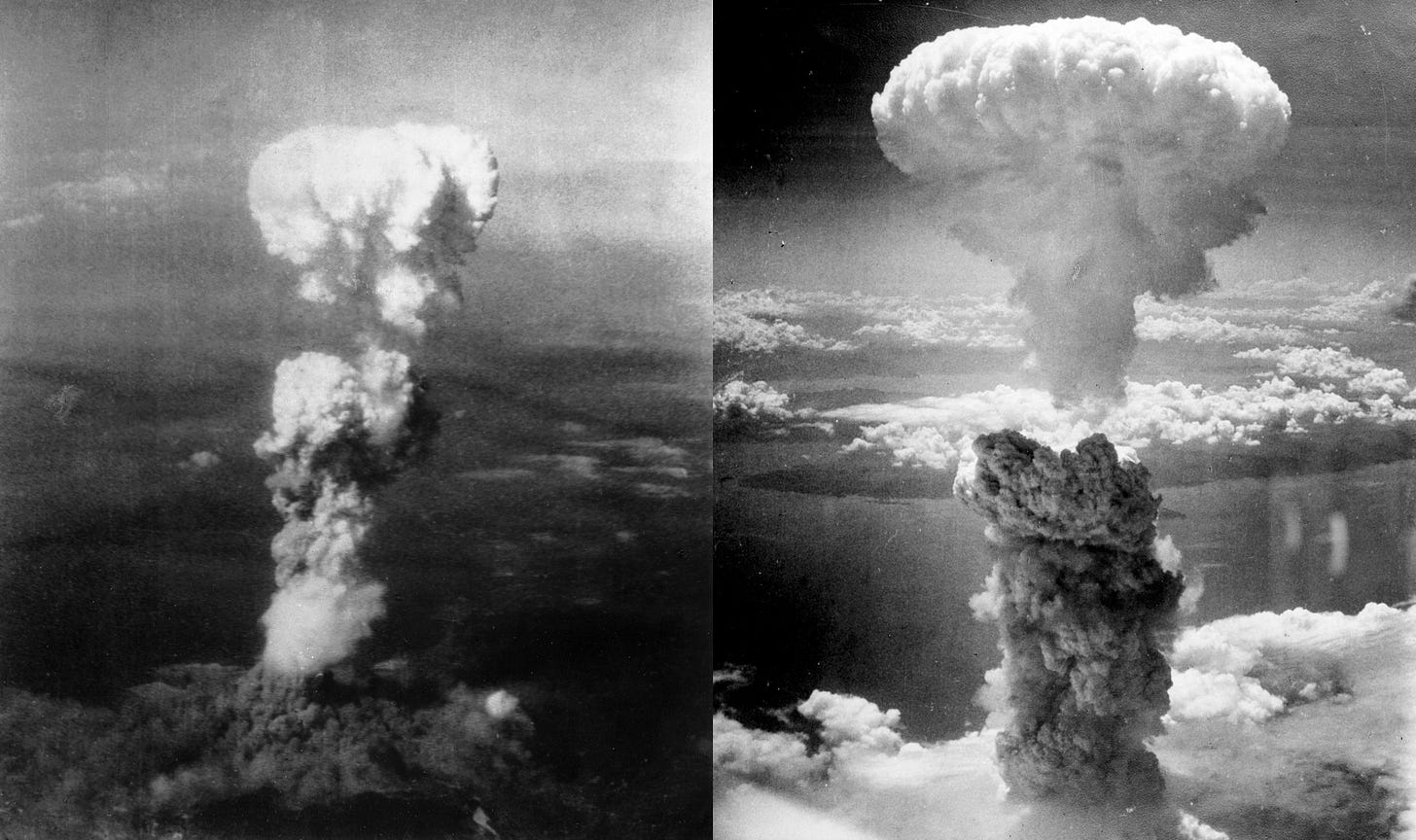

Two atomic weapons have been used in wartime, and Kenshi Hirata, a diminutive, sad-faced resident of Nagasaki, was one of a handful of people on this earth who experienced both of them.

When the bomb hit Hiroshima on August 6, 1945, Hirata was at work at the Mitsubishi shipyards three miles from ground zero. He escaped serious injury, and after wandering around the center of Hiroshima for two days, searching for his wife, he caught the first train leaving for his hometown. He carried with him the bones of his wife.

When it reached Nagasaki at 10:30 the following morning, he headed for home, a half-hour walk. His mother was relieved to see him, for she had heard that a new type of bomb had been used in Hiroshima. Hirata excitedly started describing the unearthly white flash he had observed in the sky three days earlier — when he saw it again through the front window about two miles away.

As one of the world’s leading authorities on the effects of the atomic bomb, Hirata was a good man to have around the house. Grabbing his mother, he dove under a table as their windows blew in.

“The bomb that makes this white flash must be following my every step,” Hirata thought afterward, as they cleaned up the broken glass. This time he did not go out and wander around the epicenter, his curiosity about new weapons that flash in the sky and blow out windows two miles away pretty much satisfied. He did not leave the house for weeks. “I did not want to see such sad, miserable sights again,” he said.

One had to appreciate the absurdity. Twice cursed or twice blessed? If you were A-bombed twice within three days, and survived, and went on to live a full, healthy life, would you consider yourself doubly unlucky or doubly lucky? “I felt so dishonored that I had to experience the atomic bomb twice,” Hirata said, explaining why he had not talked about this until recently. “It’s nothing to be boastful about. I could not talk to anyone about it because almost no one else met the bomb twice, so there was no one who could sympathize with me.”

I am almost embarrassed to say how much I did not know about the period in history. I was born 15 years after the war ended and learned in school how amazing America was to end that war (never learning any of the reality).

Thanks you Greg for this "Hiroshima to Hollywood" series...You have really opened my eyes.

To experience bodily an infernal catastrophe and survive is a terrible burden. But twice?