The Physicist Who Quit Los Alamos, on Principle

Joseph Rotblat walked away, then led efforts to keep The Bomb in check.

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including “Hiroshima in America,” “Atomic Cover-up,” and the recent award-winning “The Beginning or the End: How Hollywood—and America—Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.” He has directed three documentary films since 2021 for PBS (and “Atomic Cover-up” coming this fall). He has written about the atomic bombings for over forty years. You can subscribe to this newsletter for free.

Back in July 1985, when I was editor of the leading antinuclear magazine Nuclear Times, the new issue of the venerable Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists landed on my desk in NYC carrying a startling article by a physicist I’d never heard of, revealing that he had walked away from bomb work at Los Alamos on principle.

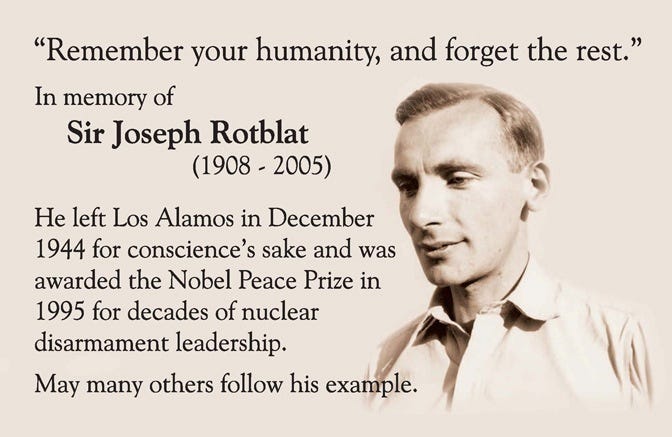

His name was Joseph Rotblat and, as it turned out, he was apparently the only scientist who resigned his position in taking a moral stand. I had wondered where he was in Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer but now we can view him in another film.

An article today at Literary Hub—which has published two of my Bomb-related pieces since 2020—reminded me about Rotblat and I’d like to excerpt from it below.

Written by Lauren Carroll Harris, it holds the headline, “Beyond Tortured Genius: Science and Conscience in Two Rediscovered Oppenheimer Films.” One of the films you may know and it has drawn a lot of post-Oppenheimer attention: The Day After Trinity, by Jon Else, a celebrated doc on Oppie and the bomb, produced for PBS around 1980 when I first saw it. So let’s stick to the second, new to me, from 2008, The Strangest Dream, from Canada, which focuses on Rotblat.

Day After Trinity includes a number of conscience-driven comments from Robert Wilson, who was the model for the character in Oppenheimer who vomits in disgust outside a party celebrating the Hiroshima blast. But Wilson, despite qualms, had stuck with the first atomic bombs to their end.

I’ll simply quote from Harris’s article covering Rotblat and suggest you read it all:

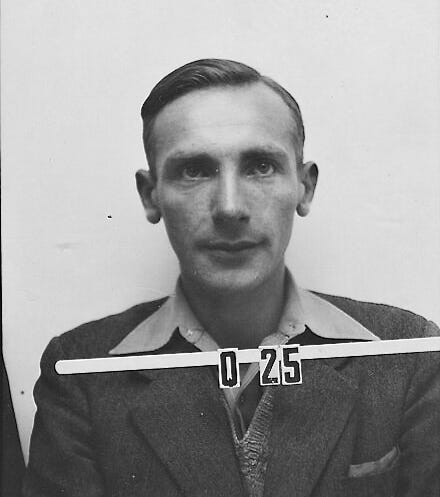

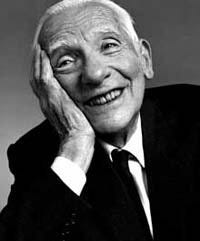

In films on the Manhattan Project, questions of conscience are commonly seen through the assenting viewpoint—that of the scientists who continued to work on the bomb, even after Hitler’s defeat. One essential perspective is obscured, black-holed in subterfuge, even. Physicist and European refugee Joseph Rotblat made crucial discoveries in the fission process, and went on to specialize in nuclear fallout. He moved to Los Alamos in 1944 but defected from the project on grounds of conscience upon learning that the Nazis could not build such a bomb. He was the only scientist to turn his back.

“If my work is going to be applied, I would like myself to decide how it is applied,” Rotblat says in the 2008 Canadian documentary The Strangest Dream. Streaming on the National Film Board of Canada’s platform, the film traces his renunciation of A-bomb development and his role in the Pugwash Conferences, where scientists and statesmen gathered to discuss the reversal of nuclear proliferation. The film renders a fairly straight treatment of its quiet subject, with the visually rich backing of a vertiginous collage of disparate forms, including spooky Cold-War era footage and clips of the Trinity mushroom cloud. Oppie is not in the film, but the narrative takes place in the fissures he helped wrench open; he lurks like an ever-present ghost behind the character of Rotblat, who stands as his angelic nemesis as he tries to transform physics into a humanitarian project. Like Oppenheimer, Rotblat was also accused of espionage, but he was eventually awarded a Nobel Peace Prize for his contributions to the disarmament campaign.

Notably, Rotblat is entirely absent from Oppenheimer, despite being described as a brilliantly offbeat individual—a “mad Polish scientist”—by a former student in The Strangest Dream. It’s a curious historical erasure and a missed chance for a dramatic clash. Then again, perhaps Rotblat is too steady and untragic, incorruptible and unmemeable for his own big moment, let alone the blockbuster treatment. Oppie’s genius wasn’t just in his Faustian bargain but in the way that he spoke and the way he held himself, quoting Hindu philosophy and smoking till the end of time. I suppose film culture is more interested in the flawed, tortured luminary than the staunch, principled dissenter or the morally engaged scientist.

Prosecuting the melancholic drama of the ingenuous mastermind requires substantial historical selectivity. Most cinema narratives hew to the oft-cited rationale for the A-bomb’s development: its function as a deterrent to a Nazi explosive. But in his essay “Leaving the Bomb Project,” Rotblat wrote, “Groves said that, of course, the real purpose in making the bomb was to subdue the Soviets… Until then I had thought that our work was to prevent a Nazi victory, and now I was told that the weapon we were preparing was intended for use against the people who were making extreme sacrifices for that very aim.” With more than a dash of elegiac melancholy, the working thesis of The Strangest Dream is that Rotblat’s moral strength insulated him against Oppie-style tragedy.

Just published: an expanded edition of my book Atomic Cover-up, now with several thousand words of mine re: the movie and the man Oppenheimer. And it’s on sale this week as an ebook for just $3.99 ($12.95 for the paperback).

Fascinating story Greg! Learning something every day. Thank you.