Why I Like Ike

Nolan does not challenge the Hiroshima narrative of justification--but Eisenhower did.

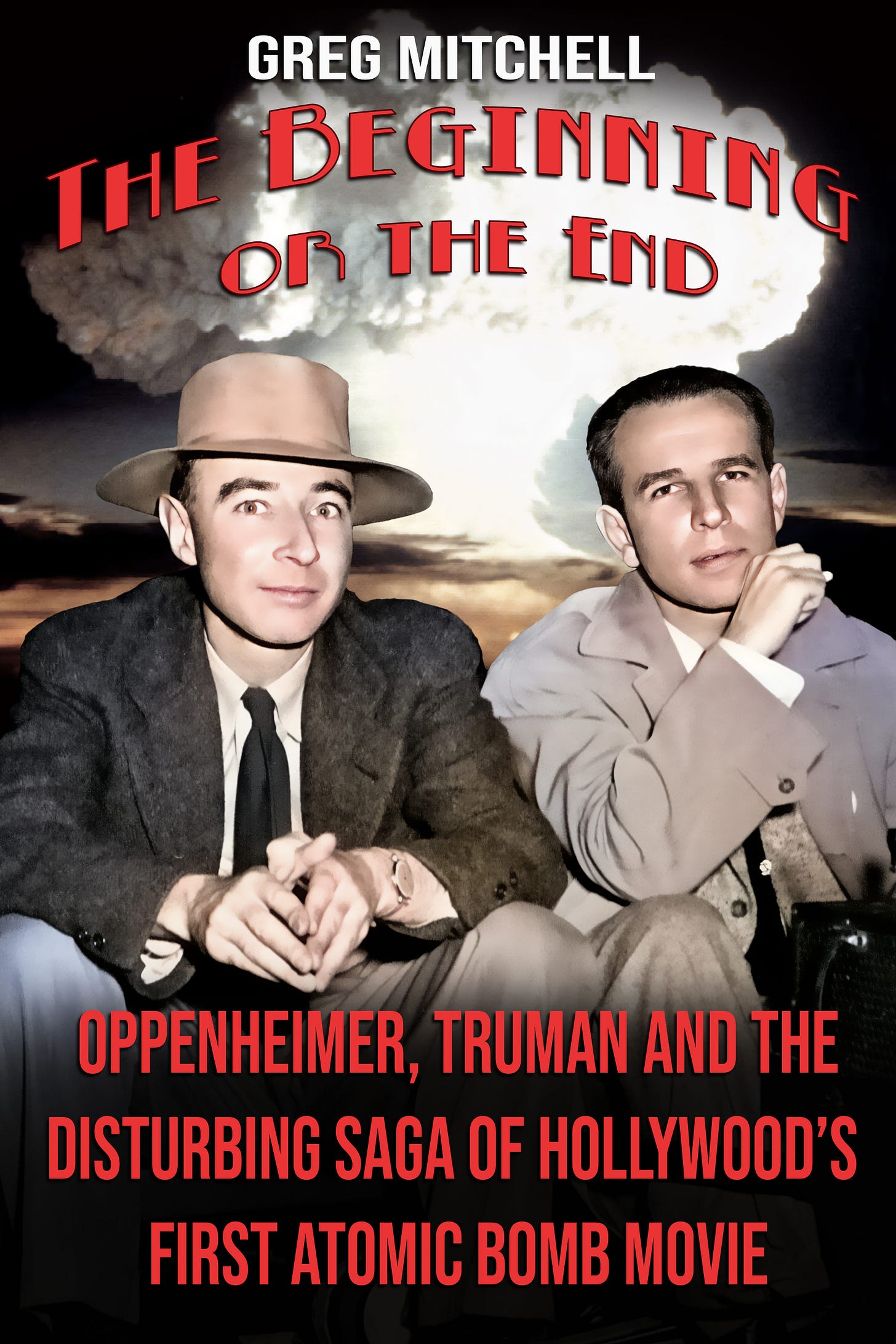

Greg Mitchell is the author of a dozen books, including “Hiroshima in America,” and the recent “The Beginning or the End,” and has directed three documentary films since 2021, including two for PBS (plus award-winning “Atomic Cover-up”). He has written widely about the atomic bomb and atomic bombings, and their aftermath, for over forty years.

My latest “Oppenheimer”-related piece just published online and in print today by Mother Jones. It’s my second there in the past week, and this time about how director/writer Christopher Nolan failed to challenge the official justifications for dropping the bombs over Japan. The previous MoJo covered the first movie about the bomb that I explore in my book of the same title, “The Beginning or the End.”

When was my first piece for Mother Jones ever? It came in 1985 and what a bookend: based on my phone interview with the man who dropped the bomb over Hiroshima, Paul Tibbets. He took the call at his company Executive Jet Aviation in Ohio. He was friendly enough. Expressed no regrets, said “you couldn’t let yourself think about the people burning up down there.” Precisely the point and also a good summary of America’s response over the past 78 years. And now Nolan, in his often fine movie, doesn’t have the courage to show what happened on the ground there.

I told Tibbets that when I’d been in Hiroshma and Nagasaki for a month the previous year, one of the survivors of the bombing—a former director of the prominent Peace Museum there—showed me letters he had exchanged with Paul a few years back. This gentleman had told Tibbets he wished to meet him and tell him he bore no ill will, he just wished they could work together to prevent any future nuclear blasts. Tibbets had expressed no regrets in those letters, either, and any meeting never happened.

By the way, in “The Beginning or the End,” I also reveal how a pilot, not Tibbets, two months after Hiroshima, re-enacted the bombing, complete with smoky mushroom cloud, for 78,000 fans at the L.A. Coliseum. No one died in that case. Tibbets himself performed the same stunt for a crowd years later.

Here’s an except from today’s Mother Jones piece:

When one attendee suggests using a “demonstration” blast instead to compel a Japanese surrender, Oppenheimer shoots this down. The Japanese will only give up, he argues, if they see the full, city-destroying effects of the bomb. And suppose it’s a dud? Or, forewarned by a demonstration blast, the Japanese are able to track and shoot down the bomber shuttling the real thing? Another panelist remarks that he might very well be in that plane. End of argument.

This forms the core of the story that has held sway since 1945, despite new evidence and compelling arguments raised by numerous historians. From Nolan’s movie, you’d never know that many historians today believe that if Truman had waited just three days after Hiroshima for the Soviets to enter the war as the US insisted, the Japanese would likely have surrendered in about the same time frame. (That bloody invasion cited in the movie was still more than three months off.) Truman himself wrote in his diary in mid-July, after the Trinity test, that when the Soviets declared war it would mean “Fini Japs”—even without the bomb.

Now, coincidentally, yesterday in 1945, we have this historical episode, as recorded in my annual day-by-day Countdown to Hiroshima at my Pressing Issues blog…

July 20, 1945: Secretary of War Stimson met several top U.S. generals in Germany. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower would years later in Newsweek write: "Secretary of War Stimson, visiting my headquarters in Germany, informed me that our government was preparing to drop an atomic bomb on Japan. I was one of those who felt that there were a number of cogent reasons to question the wisdom of such an act. …the Secretary, upon giving me the news of the successful bomb test in New Mexico, and of the plan for using it, asked for my reaction, apparently expecting a vigorous assent.

"During his recitation of the relevant facts, I had been conscious of a feeling of depression and so I voiced to him my grave misgivings, first on the basis of my belief that Japan was already defeated and that dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary, and secondly because I thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives.

"It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of ‘face’. The Secretary was deeply perturbed by my attitude."

There is conflicting evidence that Eisenhower also delivered this message to Truman. Ike would later repeat in a memoir his opposition to dropping the bomb--"that awful thing"--on Japan.